Egypt, the fascinating ancient civilization in Museo Barracco

For Ancient Rome, the separations we mentally make between Europe and Orient was not a definite border. The Romans rather thought of their empire as surrounding the Mediterranean See, thus including parts of North Africa, Middle East, Greek islands or Anatolian plateau. The lively exchanges between these regions and cultures added to Rome’s treasury more distant artifacts. Obelisks with hieroglyphs can be seen here as in Constantinople, the Eastern capital of the empire, as Egypt fascinated the Latins.

Even inside the empire, the kingdom of Cleopatra sparkled imagination and was treated with respect. Like the Greeks before them, Romans revered Egypt for its age and thought of the local gods as equivalent to their own and respectable for their endurance. So artifacts were brought on the old continent, first as booty then as souvenirs and as collectibles.

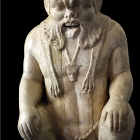

We usually know Egyptian art through findings from tombs, so we might have a distorted view of their artistic representations. The oldest proofs of Egyptian artistic work are as old as 15.000 years, contemporary to the drawings from European caves of Lascaux and Altamira. The first Egyptian sculptures were representing deities and Pharaohs as well as sacred animals.

Hieroglyphs, the writing system on the Nile, engraved or painted, also reached a state of art representing animals and abstract symbols. They were deciphered by Jean Francois Champollion, during Napoleon‘s reign over Egypt, using the famous Rosetta Stone, which had the same text in hieroglyphs and in modern writing.

Being made of wood, many ancient sculptures have been lost. Like other statues of Antiquity, they too were vividly painted and lost colors over time if preserved.

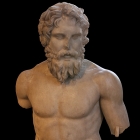

Museo Barracco in Rome is hosted by a 16th century villa. The collection includes Assyrian, a people of Mesopotamia (wall decorations from the palace of Assurbanipal at Nineveh), Greek (works of Polyclitus, a 6th century BC artist), Cypriot (votive cart and the head of Heracles), Egyptian, Phoenician, Etruscan and Roman art.

The passionate collector, Giovanni Barracco was a nobleman and senator in the 19th century. His family sponsored Garibaldi’s liberation of Naples. With the advice of Wolfgang Helbig, the director of the German Archaeological

Museum and of Ludwig Pollak, an art expert, Giovanni Barracco started his collection with objects excavated in Rome. Barracco donated his collection to Rome’s municipality since he had no descendants. The villa in which the city hall gave to host the donations of Barracco is still the place of this museum today, on Corso Vittorio Emanuelle, just across the street from another public museum, Museo di Roma in the palace of Saint Giovanni of the Florentines. Barracco continued to add up to the collection even after it became public property.

- Home Page

start page - Architecture

landmark buildings - Sacred architecture

places of worship - Nature

landscape photography - Concert

performing artists - Christmas

Santa Claus pictures

- Jooble

jobs for photographers - Escape

an out of control blog - Merry Christmas

The best organizer of Christmas parties - Astro photo

Eclipse hunting and astrological photography